At the end of the year, reflection is de rigueur. Calendars close. Rituals repeat. Regrets become bygones. People speak in the language of fresh starts and clean slates, as if January can erase what the body remembers. If only. ’Tis the season of good intentions and manifestations. It is the season of hope. This year, I find myself holding on to hope out of habit but seeking something more sturdy. I'm scanning for solid ground to land on.

For the last eighteen years, Christmas centered around my daughter. Never a fan of commercialism, our holidays focused on activity together—exploring the melding of Islam and Christianity in Malta; dancing with Chiang Rai hill tribes and wandering Buddhist temples with Colin; learning to ski in Braunwald; Māori feasts and climbing volcanoes in New Zealand; singing carols in St. Patrick’s Cathedral; or catching first powder tracks in Breckenridge and Jackson—all before French toast and bacon. Each day ended the same way: reading new books by the fire. When your family is just two, Christmas becomes about doing something together you might not otherwise do. It is a time for that elusive and often underrated sacred pause.

This year’s Christmas was quiet. Contemplative. Solitary.

For months now, I have felt myself circling, like the hawks I watch ride the updrafts near the cliffs by Hublein Tower—moving in wide arcs above ground that does not yet feel safe to touch, surveying the landscape, peering into the shadows, all while yearning to touch the sky. Anyone who has flown knows the sensation: the plane keeps turning while conditions below remain unclear. From inside the cabin, the mix of fear and impatience can feel interminable. From the cockpit, however, it is deliberate. Circling is not failure; it is judgment. It is what pilots do when visibility is compromised and a forced landing could cause harm. Better to wait. Better to get everyone safely home.

Home, I’ve realized, is not a place I failed to find. Home was wherever I was with my daughter. I endeavored to make the journeys themselves our home—to make home a state of mind. When I am asked why I never settled, or reminded that I “made my choices,” this is what comes to mind. I notice the urge to ask why those who say it allowed themselves to settle, to stagnate, and to grow complacent. I never actually say that out loud. I wonder why some feel it is ok to comment at all. What I know instead is this: after living all over the world, I am skilled at making a home wherever I find myself. Home is not a destination. It is a practice I returned to—sometimes in motion, sometimes in exile, sometimes circling while waiting for permission to land.

We like to tell ourselves that home equals permanence. But permanence is an illusion we allow ourselves so that we feel in control. I learned young what that saying about the best laid plans really means. Coming back to my hometown this year was not a sentimental homecoming. It was a re-entry—a full-circle return after decades of movement. The streets are familiar. The geography is known. There is comfort in that. There are memories around every corner. And yet everything feels subtly altered, as though I had been living in a parallel version of my life and only now crossed back through a thin seam. When I see people I knew in my youth, I am startled by how little they resemble my memory. Then I catch my reflection and remember how much time has passed.

I have lived through uncertainty before—my dad’s ten year cancer journey, Colin’s coma, job loss, war zones, flood evacuations—real danger—and I always believed there would be a safe landing. Learning to sit inside uncertainty is one of life’s harder disciplines. This year has felt like sustained turbulence: no clear altitude, no horizon, no reliable sense of when or how it will end. Like flying inside storm clouds, I have often lost my sense of up and down. What I understand now is that circling cannot last forever. Fuel is finite.

In 2007, I gave birth alone, knowing that I would. I prepared for it like I would have a championship lacrosse game. There were doctors and nurses, of course, but they were doing their jobs. I was bringing a new life into the world. It was powerful. Primal. Sacred. It was April in Aspen—shoulder season, heavy wet snow falling hard enough to close the runway. If something went wrong, there would be no quick flight to a larger hospital. Labor was long. There was meconium. Real risk. Birth plan altered. In the wee hours my daughter arrived quietly and was handled with urgency and care.

The morning after her birth, holding my tiny daughter in my arms, I looked out the hospital window and saw a red fox flash across the bright white snow. It paused—vivid and poised—long enough to meet my gaze before trotting away with a swish of its bushy tail. I noticed it then, and I remember it now. In both Japanese and Irish traditions, the fox is a guide at thresholds, a creature that moves between worlds—spirit and human, wilderness and settlement—without belonging fully to either. It survives through attention, timing, and discernment rather than force. The fox did not linger. It did not look back. It crossed the snow cleanly and disappeared. Its presence felt as if it was noting a crossing already underway. I turned back to the new life in my arms, knowing I would be learning how to guide her across many such thresholds myself.

I turned back to my daughter and named her Niamh—after the princess of Tír na nÓg, the land of youth in Irish mythology. She is the woman who rides over the sea on a white horse, crossing between worlds, choosing both love and adventure for herself over safety and stasis. In the old stories, waves are often described as white horses, carrying her between realms. Tír na nÓg is a place without aging or decay—a place of vitality, courage, and belonging. It held all the things I wanted for my daughter. When Niamh was small, she believed completely that she was that princess. I read her the story so often it lived in her bones. Even her name carries a crossing—Niamh, sounding like nieve, the Spanish word for snow. She is of the sea and of the snow. A child born between elements. And she is most at home in both.

A week earlier, heavily pregnant, I had stayed alone in a hut at Snowmass Monastery. I slept. I meditated. I prepared. Each evening I waddled past elk in the fields to the stone chapel where I let myself be carried away by the somatic power of monks chanting vespers. I had very little. I had no plan. I was dismissed by my child’s father, by my employer, by my family. And still, I believed all would be well—not because the ground was safe, but because I trusted myself and the love I already felt for the life that was making its way toward me.

When people speak easily about “the choices we make,” they often imagine a level runway and plenty of fuel. They imagine a warm car waiting in the pickup lane, smiling faces at the arrivals gate. They assume time, support, and room for error. But some decisions are made while circling, with incomplete information and very little margin. In those moments, choice looks less like preference and more like responsibility. You do what you must. You keep flying because you are accountable for the life you are carrying and the future you are trying to protect. Much of my life has been shaped by decisions made under those conditions. I chose love. I chose courage. Not because they were ideal options, but because they were the ones available to me.

In recent years, in the days before Christmas, my daughter and I added Love Actually to our holiday movie playlist. Much of the film is outdated fluff—power imbalances disguised as romance, longing framed as virtue, waiting to be chosen. But the candid opening and closing scenes at Heathrow arrivals have always moved me. Real people filmed without performance. Faces lighting up as loved ones appear. We don’t know their histories or their fractures. What we see is simple and true: people choosing to show up. We are reminded of the privilege it is to be present for someone—and the good fortune to have someone be present for you.

Over time, I’ve learned that love isn’t proven by endurance or by how long someone tolerates absence. It’s revealed by who arrives, and how, without keeping a ledger or demanding something in return. Love, at its most honest, is choosing to show up. Again and again.

When my daughter was small, we watched Brave on repeat. She loved Merida’s fierce independence. I was drawn to the mother who learns—too late and painfully—how easily protection becomes control. Current circumstances make me wonder if the film was fate’s foreshadowing. In that tale, the mother becomes a bear not as punishment, but through her own fear and misunderstanding. The spell breaks not through conquest, but through recognition.

I have seen bears up close. A grizzly crossed my path on Mother’s Day last spring as I walked around Jackson Lake—massive, alert, looking for food and uninterested in dominance. At that same moment, my daughter was in the sky above, crossing a continent and an ocean back to her father’s home—Ireland. The bear did not charge or retreat. It ambled across my path while I held my breath. Strength does not always announce itself as danger. Sometimes it arrives as a reminder of what we contain within us.

I once heard that some Indigenous peoples believe when humans move too fast, the body can arrive before the soul, and the soul needs time to catch up. I believe this is true. I have felt it myself. I have lived much of my life in motion, crossing borders and systems, always adapting, always arriving efficiently. I never learned how to arrive whole as some part of me was always left behind. Perhaps this season of circling is not failure but reintegration. I was drawn to return here perhaps because this is where my soul knows how to find its origin point. Perhaps pieces scattered across years and places are finally being given time to find their way home to me.

When some say that I made my choices, I don’t disagree. I chose love. I chose courage. I chose to keep showing up without keeping score. I am not here because my journey failed. I am here because journeys sometimes pause. If there is a landing ahead, it will be because conditions changed. Until then, I will keep circling—not in indecision, but in care. Scanning the landscape for a clearing. Not as a performance, but as a witness. Not as a plea to be chosen, but as a refusal to disappear.

At the end of this year—this year of the snake—this is what I know: I am still here. I am telling the truth in a form that can hold it. I am allowing time for all of me to arrive. And I will keep showing up, because that is what I can do.

Prologue

Prologue

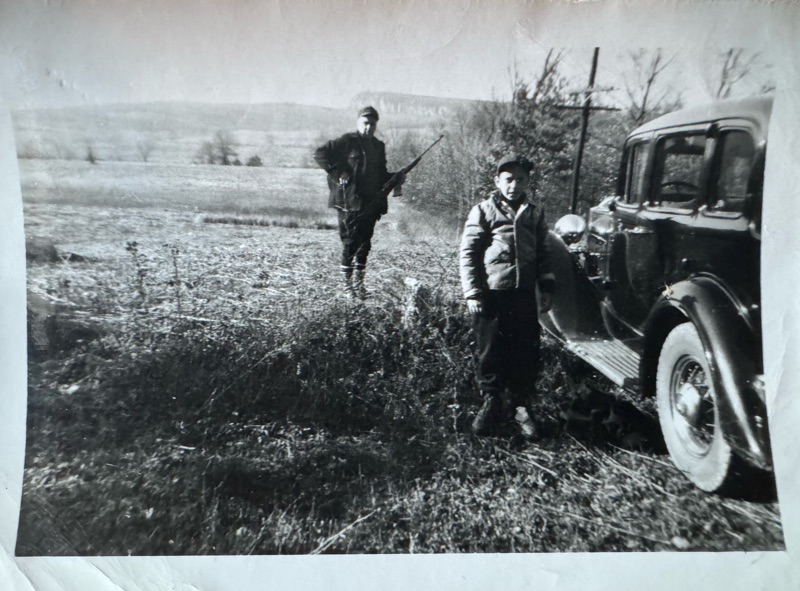

Grandpa Keating, Uncle Jack. Taken by my father 1940. New Palz, NY.

Grandpa Keating, Uncle Jack. Taken by my father 1940. New Palz, NY.