Religion, Violence, and the Work of Peacemaking:

For more than three decades, I have lived and taught at the intersection of religion, conflict, and education. My work as an international educator has taken me from El Salvador to Libya, Thailand to Indonesia, Ireland to Japan, Italy, and finally to the United Nations International School in New York City. Across these contexts, I have encountered the deep entanglement between faith, identity, and power—themes that run through this module’s readings and lectures. Long before I enrolled at Hartford International University for Religion and Peace, my professional and personal life had already been a study in interreligious encounter, violence, and reconciliation.

My understanding of religion and violence began not in a university but in a Catholic elementary school in West Hartford, Connecticut-not too far from HIU. At St. Timothy’s, we prayed for the Irish hunger striker Bobby Sands and for the American nuns murdered in El Salvador. These distant conflicts became, for me, moral puzzles: why was faith so often linked to suffering? That question would guide the next thirty years of my life.

Years later, I found myself teaching history and literature at Escuela Americana in El Salvador (1997–1999), a school affiliated with the conservative ARENA Party. Outside the walls of that institution, I came to know a group of Irish NGO workers who were serving rural campesino communities aligned with the FMLN. Among them was Dr. Mo Hume, now Professor of Latin American Politics at the University of Glasgow and daughter of the Nobel Peace Laureate John Hume. Through Mo, I began to see the parallels between postwar El Salvador and Northern Ireland: both societies scarred by histories of colonization, both wrestling with violence carried out in God’s name.

Irish Peace Bell at Trinity College in Dublin placed in Memory of the Jesuits murdered in El Salvador.

Through Mo Hume and our friends I learned of her father's edict that “we should spill our sweat, not our blood,” and about his vision of the European Union as proof that former enemies could build peace through cooperation rather than conquest. She also told me about the Irish School of Ecumenics at Trinity College Dublin, where scholars and activists were working at the intersection of theology and peacebuilding. Years later, I would attend that program myself, earning my M.Phil. in International Peace Studies (2004–2006). When I arrived, I noticed a large Peace Bell in front of the school, dedicated to the Jesuits murdered at the Universidad Centroamericana (UCA) in El Salvador—a physical reminder that the moral struggles of Latin America and Ireland were intertwined.

Inside the UCA chapel, the traditional twelve Stations of the Cross are replaced with images of contemporary suffering: the crucified Christ mirrored in peasants, laborers, and martyrs of El Salvador’s civil war. The art reimagines the Passion as a story of political and social violence, insisting that salvation cannot be separated from justice. That choice—the replacement of the ancient narrative with a modern one—embodies the idea that violence and faith are not historical opposites but coexistent realities, forever wrestling for meaning.

During my studies at Trinity, I wrote an essay on Just War Theory, exploring how President George W. Bush invoked St. Augustine to rationalize preemptive war in Iraq (Moseley 2020). At the time, Colin Powell was calling the U.S. strategy “Salvadorization,” echoing the counterinsurgency tactics the United States had supported in El Salvador decades earlier. My research into that period revealed that many Salvadorans recognized the methods used at Abu Ghraib—they had endured similar torture, taught by U.S.-trained officers at the School of the Americas. The moral irony was unbearable: the same theology once used to restrain violence was now being used to sanctify it.

Religion, as the lecture Blaming Religion (Vimeo 2021) and Hedges’s Understanding Religion (2021) both underscore, is too often scapegoated for violence whose real roots lie in power, inequality, and identity. My own experience confirmed this. In El Salvador, faith was used both to bless the oppressor and to inspire the oppressed. The question was never whether religion caused violence, but which interpretation of faith people used to justify or resist it.

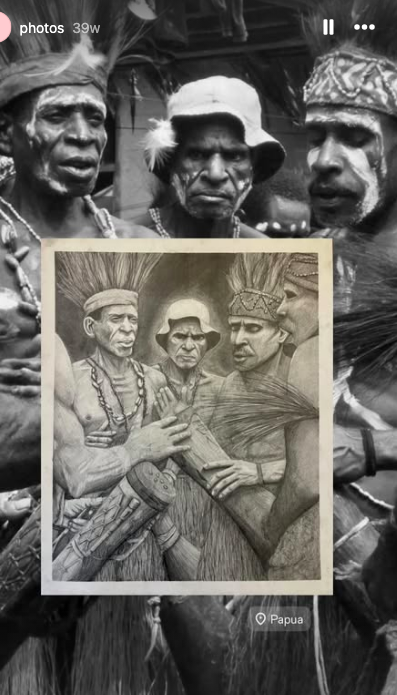

The postcolonial lens offered in Postcolonialism and Decolonial Theory (Vimeo 2021) helped me understand how global education—my own field—has also been shaped by missionary and imperial legacies. Teaching in Christian-founded international schools in Japan, Thailand, and Rome revealed how education often carries the imprint of colonial hierarchy, even when cloaked in benevolence. At Ruamrudee International School in Bangkok, founded by Redemptorist priests, I watched Thailand’s “Red Shirt” and “Yellow Shirt” movements invoke moral and spiritual language to justify political violence. Later, in Indonesia, I taught at a school attached to Freeport-McMoRan’s Grasberg Mine in West Papua—a stark example of how corporate and colonial interests perpetuate economic violence long after the missionaries have left.

These experiences have taught me that violence and religion cannot be disentangled from power. To teach history or ethics in such contexts is to confront how narratives are used to sanctify domination or inspire liberation. In Politics, Peacemaking, and Power (Vimeo 2022) and Sometimes It’s Ugly (Vimeo 2022), this paradox is laid bare: the same scriptures that fuel exclusion can also ignite the moral imagination necessary for peace.

When I later taught at the United Nations International School in New York City (2017–2019), I found myself in a community that lived the practice of interreligious understanding. Every classroom conversation about justice or belonging became an act of peacebuilding. My students—children of diplomats, aid workers, and teachers, all third culture kids like my own daughter, helped me see that moral education is itself a form of nonviolent resistance. It cultivates empathy across belief systems and prepares the next generation to engage difference without fear.

Yet even as I taught about reconciliation, I carried a more intimate understanding of conflict. My daughter’s father grew up in Dundalk, a border town in Northern Ireland where British Army helicopters once landed in his family’s fields in pursuit of paramilitaries. While I was a girl in Connecticut praying for Bobby Sands, he was living in the shadow of the Troubles. These parallel lives—his surrounded by violence, mine shaped by the moral distance of prayer—eventually converged in our shared commitment to understanding the human cost of division.

Religion, violence, and peace have thus never been abstractions for me. They are the throughline of my life’s work and experience. What this module has offered is not revelation but resonance—confirmation that the frameworks of postcolonial critique, moral theology, and interreligious ethics I first encountered in my M.Phil. remain essential today.

Today, the question of whether war can ever be just has become deeply personal. My daughter is now a cadet at West Point, preparing to serve in a world still marked by moral ambiguity and global conflict. Watching her train in ethics and leadership reminds me that Just War theory is not an abstract exercise—it is a living moral framework that shapes decisions with life-and-death consequences. My hope is that I have provided her with a life experience that will inform her and guide her to lead with compassion and humanity. I find myself returning to Augustine and Aquinas, to the belief that war may be justified only to protect the innocent, and yet also to the haunting awareness that violence always exacts a spiritual cost. History has taught us that there are innocents on all sides of a conflict. Perhaps the real challenge is not determining why or how or when war is just, but ensuring that those who fight—and those who send them—never lose sight of its human toll.

Now, as I study Chaplaincy at Hartford International University, I recognize how this journey has come full circle. The classrooms where I once taught about the world’s brokenness have become the foundation for a ministry of accompaniment and healing. Every school, every student, every conflict has prepared me to serve as a bridge between worlds of faith and suffering. Religion is neither inherently violent nor inherently peaceful—it is the vessel through which humanity seeks meaning in the face of pain. My vocation now is to help transform that search into compassion, justice, and peace.

References (Chicago Author-Date)

Hedges, Chris. 2021. Understanding Religion. Hartford International University. Moseley, Andrew. 2020. “Just War Theory.” Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://iep.utm.edu/justwar/Links to an external site.

“Blaming Religion.” 2021. Vimeo, FALL 2021, 6. https://vimeo.com/592342147Links to an external site.

“Postcolonialism & Decolonial Theory.” 2021. Vimeo, FALL 2021. https://vimeo.com/634702664Links to an external site.

“Politics, Peacemaking, and Power.” 2022. Vimeo, HIU 2022, 6. https://vimeo.com/778924615Links to an external site.

“Sometimes It’s Ugly.” 2022. Vimeo, HIU 2022, 6. https://vimeo.com/778919589Links to an external site.

“Waging the Beautiful Struggle.” 2022. Vimeo, HIU 2022, 6. https://vimeo.com/768092631Links to an external site.

Photo by Niamh Keating

Photo by Niamh Keating