Reflecting on my time in West Papua and the readings for this week, I find that my experiences living and working with Freeport McMoran — teaching at the company’s expat school in Kuala Kencana from 2015-2016 — offer a lens through which to understand the ecological grief and displacement discussed by Aph Ko and Joanna Macy. These readings resonated deeply with my lived experience outside of Timika and the nearby villages of the Kamoro people.

Reflecting on my time in West Papua and the readings for this week, I find that my experiences living and working with Freeport McMoran — teaching at the company’s expat school in Kuala Kencana from 2015-2016 — offer a lens through which to understand the ecological grief and displacement discussed by Aph Ko and Joanna Macy. These readings resonated deeply with my lived experience outside of Timika and the nearby villages of the Kamoro people.

At the time, I lived in a guarded compound, where the daily realities of safety protocols — armored buses and armed guards — underscored the conflict in the region. Behind this security, the extraction of gold and copper from the Grasberg Mine was not just economically important but also deeply disruptive to the Kamoro people's way of life. As a teacher in this remote region, I often saw the disconnect between the high salary I earned and the systemic struggles of the Kamoro, whose land and culture were being torn apart by the mining operation. The company’s operations are a modern example of the colonial processes Aph Ko critiques in her work. The racial and cultural exploitation, where Indigenous people’s land and personhood are sacrificed for profit, is a central theme of Ko’s argument — one that was all too evident in my experiences and highlighted by the work of Kal Müller.

As Aph Ko discusses in Racism as Zoological Witchcraft, colonialism is deeply tied to the dehumanization of Indigenous peoples, and this is a pattern that still plays out in resource extraction industries like the one operated by Freeport McMoran. The Kamoro’s grief, however, is not just environmental; it is deeply tied to historical displacement and economic oppression. In visiting the Kamoro community, I saw firsthand how Freeport’s mining activities had displaced people from their ancestral lands and poisoned their sacred river. Despite the company’s reassurances, I could see the toxic damage firsthand, and the rivers’ ecological health was visibly deteriorating.

As a teacher, I was in a unique position to understand both the privileged perspective of being a foreign worker for a corporation that profits from this destruction, and the marginalized perspective of the Kamoro. These roles allowed me to reflect deeply on the concept of eco-grief, which Joanna Macy discusses in The Work That Reconnects. I began to understand that the grief the Kamoro were feeling — and that I began to share in — was not just an emotional response to environmental devastation, but also a deeper, cultural loss. This grief, shaped by centuries of colonialism, was tied to the very foundations of their identity — their relationship to land, river, and culture, all of which were being threatened by Freeport's extraction.

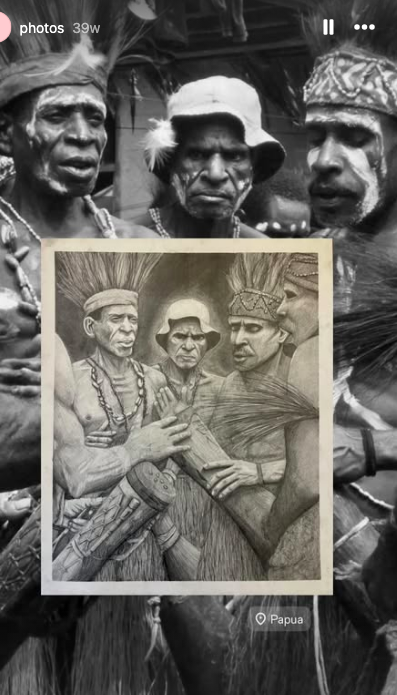

One of the highlights of my time in West Papua was the opportunity to spend a day with the Kamoro, learning their cultural traditions, including their drumming. My daughter, who was 8 at the time, captured a powerful photograph that she recreated for her AP art project last year: Kamoro men drumming, an image that became emblematic of the resilience and cultural survival of the Kamoro people. (See photo above)This moment connected deeply with Joanna Macy’s reflections on cultural healing and resistance. In Macy’s work, she encourages us to recognize grief as an expression of resilience, and I saw this in the Kamoro’s survival through their art, music, and language, despite the challenges they faced.

Through Kal Müller’s anthropological work with the Kamoro, which helped us navigate our visit, I was able to understand that Jared Diamond's ideas in Guns, Germs, and Steel — how resource extraction reshapes the course of Indigenous peoples’ lives — were not just theoretical. Müller’s research and Diamond's historical framework revealed the ongoing consequences of resource extraction, showing how the Kamoro's culture was not just being displaced physically but erased in the global economy. Müller’s efforts to help foreigners understand the Kamoro were crucial in preserving the people’s voice and sovereignty, much like Diamond's global perspective on colonization and resource extraction.

Müller’s ethnographic work provides a powerful lens through which to view the eco-grief discussed in the readings. He documents how the Kamoro’s cultural identity is deeply tied to their land and how the destruction of their ancestral environment by the Grasberg Mine has displaced them, both physically and psychologically. As Joanna Macy describes, grief is not just an emotional response to loss, but a recognition of deep connections to the land, people, and culture. The Kamoro's grief is therefore both environmental and cultural, reflecting eco-grief as described by Macy, and a clear manifestation of the colonial relationship between resource extraction and Indigenous displacement.

When I consider Aph Ko’s discussion of grief as a racialized and colonial experience, I see how the Kamoro’s sorrow goes beyond environmental loss. Their grief is tied to a historical pattern of exploitation — where colonialism and resource extraction have historically denied their humanity. The Kamoro people's grief, as well as their resilience, are part of the legacy of colonial systems that continue to affect Indigenous communities across the globe.

The devastation caused by the mine is well-documented, such as in The Guardian’s photographs of West Papua, showing the toxic waste and ecological destruction that continues to damage the land.

This destruction, combined with the historical trauma experienced by the Kamoro, creates a vicious cycle of grief and loss that is rooted in colonial violence. This collective eco-grief, as described by Joanna Macy, can only be fully understood when seen through the lens of colonialism and racial oppression, which is still ongoing in places like West Papua.

As I reflect on the eco-grief described in the readings and my experiences in West Papua, it is undeniable that the very copper and gold extracted from the Grasberg Mine are essential components of the technology that powers our daily lives. Copper, for example, is a core element of the smartphones, computers, electric cars, and renewable energy technologies we use every day. Gold, too, is integral in the electronics we rely on, including the devices in our pockets. These minerals, extracted at great human and ecological cost, fill a global demand that is essential to modern life — but this comes at the expense of communities like the Kamoro, who suffer displacement and loss of their ancestral lands.

This stark reality forces us to confront the uncomfortable truth that our everyday lives are sustained by the extraction of these resources, often from lands that belong to marginalized peoples. By recognizing this, we must ask ourselves: How do we change our behaviors, our consumption habits, and our global economic systems to reduce the harm caused by these resource extraction practices? The environmental and cultural damage inflicted on the Kamoro people can only begin to be addressed when we confront the systemic inequalities that perpetuate this cycle of extraction and exploitation. If we want to change the impact on the environment and on Indigenous communities, we must also change the way we live and the resources we consume.

Related Blog Posts:

Kamoro Tribe: Mware

Papuan Perspective

References:

Ko, Aph. Racism as Zoological Witchcraft: A Guide to Getting Out. North Atlantic Books, 2020.

Macy, Joanna. Active Hope: How to Face the Mess We're in without Going Crazy. New World Library, 2012.

Diamond, Jared. Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies. W.W. Norton & Company, 1997.

Müller, Kal. The Kamoro. 2022.

The Guardian. "West Papua: Verdant Heartlands Devastated by Mine Waste," November 2, 2016. [https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/gallery/2016/nov/02/west-papua-indonesia-verdant-heartlands-devastated-by-mine-waste-in-pictures](https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/gallery/2016/nov/02/west-papua-indonesia-verdant-heartlands-devastated-by-mine-waste-in-pictures

No comments:

Post a Comment