Prologue

Prologue

My father wrote this piece in October of 1989. At first glance it looks like any careful submission: clean typeface, a word count at the top, his address typed neatly in the corner. He prepared it for publication. He wanted it to live somewhere beyond his desk, beyond our family, beyond the years he knew he might not have.

He also mailed a copy to me.

At the time, we were not in close contact. I was a college sophomore, overwhelmed and angry, and we had slipped into one of those quiet distances families sometimes fall into—no rupture declared, just a widening space neither of us knew how to cross. I didn’t yet understand what it meant to write into distance, or to send something forward in the hope that it might one day be received with a softer heart.

I couldn’t see then the care with which he built this piece—the way he arranged memory and landscape, the way he placed his own father inside the Catskills and North Africa, the way he saved the quiet truth of what he knew was coming for the final lines, after stripping everything else down to what mattered most. I didn’t yet recognize it as a map of where he came from, or a map he hoped I might someday learn how to read.

Over the years, and after countless moves, I lost almost everything else he sent. But this story survived. Whether consciously or not, this was the piece I kept—the one I wasn’t ready for then, but needed later.

Looking back now, I see how much of my own life unfolded inside the vocabulary he left behind: the walks along reservoirs, the pull toward mountains, the curiosity about distant landscapes, the years I spent living in parts of the world his father once moved through in wartime. Even my writing—rooted in water, memory, and movement—echoes his cadence.

There is a throughline in our family: nature, story, home.

His father passed it to him.

He shaped it into this piece.

I carried it forward without realizing it.

And it continues, altered but intact.

Our family’s story begins on particular ground: the hills and waterways of Ulster County, New York, where the first Keatings and Roaches are buried—immigrants who carried their losses across the Atlantic from Ireland in the 1840s and began again in a landscape not entirely unlike the one they left. My father grew up in the shadow of the Catskills, learning marksmanship from his own father, who served in the Army Corps of Engineers during the war, building transport routes across North Africa and Italy. A quiet, practical kind of service—creating pathways.

Last month, I found this manuscript again, tucked among my old college papers. Earlier that day, I had been walking the reservoir trail he once knew, asking—almost out of habit now, and at roughly the same age he was then—for some sense of direction. The timing of the rediscovery felt precise rather than dramatic, like an echo answering an earlier call. Not instruction, exactly, but orientation.

What strikes me now is how intact his voice remains. The dry humor. The attentiveness. The way so many of these stories were ones I heard him tell over the years, especially when family gathered and memory loosened its hold. On the page, he sounds unmistakably like himself.

When he sent me this story, I couldn’t fully absorb what he was telling me—especially the way he closed it, naming what he knew lay ahead. I was young, and the weight of it exceeded what I could hold. He died in May of 1991. Only now do I understand that this, too, was part of his care: not explanation, but truth offered in his time, to be understood in mine.

My father didn’t leave a large archive. A few photographs. A painting he made of me and my cat. And this story. But writers write because they seek witness—because they want their way of seeing to be met, understood, and held by someone beyond themselves.

I share his work now in that spirit. Not to reinterpret it or explain it, but to place it where it can finally be seen. This is my way of honoring him—by letting his words stand, and by offering the witness he once hoped for.

Here is his story, exactly as he wrote it.

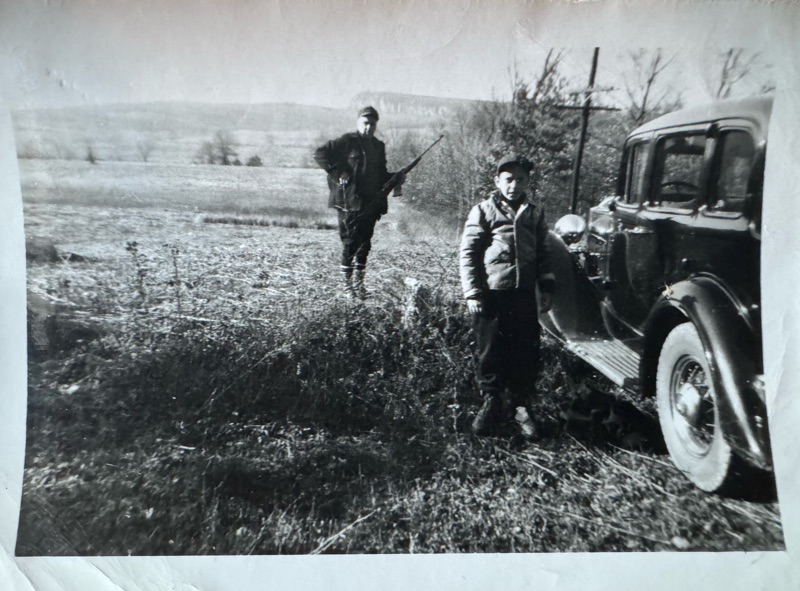

Grandpa Keating, Uncle Jack. Taken by my father 1940. New Palz, NY.

Grandpa Keating, Uncle Jack. Taken by my father 1940. New Palz, NY.

Some Days in the Woods

Stephen J. Keating, Jr., P.E.

2835 Words • Simultaneous Rights

© 10/2/89

Dad, who delighted in hunting whether for deer, pheasants, ducks, partridge, woodcock, rabbits, squirrels, introduced me to the excitement of the hunt at age 12 along with my brother Jack, age 10. He also made us aware of the sheer joy of just being in the woods, fields, wetlands, and stream courses to drink in their beauty and inhale their fragrance.

Unfortunately for Dad, on that first expedition with us, the deer Jack and I spooked in a fallow, overgrown meadow just below Phoenicia, New York, ran by us—not him and his .30–30.

Dad was a crack shot, especially on moving targets, and passed on some of that expertise to Jack and me. I never did equal his proficiency with snap shots on a leaping, hill-climbing deer, though I did end up as top rifleman in my regiment later; partly due, I believe, to Dad’s insistence that my first gun be a .22 single shot. I had to learn to get the squirrels on the first shot.

When Dad’s reserve Transportation Corps unit was called up in 1942, the hunting—for me at least—ended for three years except for plinking with the .22 when I could get ammo. He, however, through his contacts with the French Colonial Officers in Morocco with whom he was working to put the railroad into operation from Casablanca to Marrakech, and over the Atlas Mountains to Algeria to supply the troops at the front, had some unusual hunting experiences.

At one point some Arab sheiks invited Dad, some fellow American officers, and French Foreign Legion officers to join them in a wild boar hunt. As a young man, Dad had owned a beautiful Arabian mare and was right at home with the horse the sheiks provided. However, the comfortable feeling evaporated when the Arab bearers and beaters passed out a lance per officer—no guns.

In response to a nervous question from one of the American officers as to what happened if the lance broke, was dropped, or the thrust was ineffective, the sheik replied that then the boar (up to 400 pounds of pure, raging meanness with 8-inch razor-sharp tusks to match) got your horse—and you. Now that was sport! The game, at least, had an excellent chance not only of survival but of becoming the hunter instead of the hunted.

Dad came back after service in North Africa, Italy, France, and Belgium/Luxembourg with five campaign stars, but never again seemed to have the same enthusiasm for shooting at living things. I guess he had seen the evidence of too many humans who’d been hunted and slaughtered.

However, we did have some fun times interspersed with a few moments of terror in the woods, fields, and elsewhere. But they actually began before he arrived home from the European theaters, having accumulated the requisite number of service points for discharge.

A friend of mine, Charlie, from the community of Pine Hill in the Catskills, and I, while juniors in Kingston High School, decided to have a try at deer hunting. But little or no sporting ammunition was available as World War II wound down, so we dug out some pre-war #6, 12-gauge shotgun ammunition, and I made a plaster-of-Paris mold of a marble that just fit in the full-choke barrel of my Model 21 Winchester double-barrel.

We then scrounged up some lead from our toy soldier molding kit that we had outgrown and proceeded to pour “ounce” balls, file them smooth until we were sure they fit through the muzzles, and then uncrimped the #6 shells, poured out the shot, and inserted one ball in each shell. For want of any other wadding, we put the #6 cover back in.

And then we went up Belleayre Mountain near Pine Hill, NY in a light snow and proceeded to spook a deer within an hour. Our shots drew blood, but the deer could still run—and did—with us in hot pursuit until the buck ran into another group of better-equipped hunters who opened up en masse.

It sounded like the second battle of the Marne. We arrived at the scene to find a pile of steaming entrails in the snow and the marks left by the deer as it was dragged down the mountain.

Several weeks later, some other high-school buddies and I decided to go duck hunting. Our strategy was to approach a slow-moving, wide stretch of the Esopus Creek near Marbletown, NY from widely separated points and then work our way along the stream toward each other in the hopes of flushing ducks along the valley. This meant low shots as the ducks began to rise, but we felt that we’d be far enough apart that the #6 shot would be harmless before it reached us.

As the first opportunity to shoot at a low target some distance off came and I was swinging on it, a high-flying duck came almost directly overhead and I swung on it instead. As I fired, it exploded and came down in pieces, one wing fluttering to the ground some distance from the rest of the carcass.

Yes—you guessed it. One of the homemade “ounce ball” shells with the #6 crimping had gotten mixed in with the legitimate #6s. There is no question in my mind that this fast, high-flying duck was guided to that spot by a higher power.

Then, when Dad arrived home with several other Transportation Corps officers via a stripped B-17 that hopped from Prestwick to Gander, etc., we organized our first real hunt. Dad and one of his contemporaries along with my brother, myself, and several high-school friends rented a small cabin at the foot of Woodland Valley east of Shandaken and Big Indian in the central Catskills.

Dad, through his many contacts with the “natives,” whom he knew because of his railroad responsibilities (West Shore Division of the New York Central System, the Wallkill Valley Branch, and the Catskill Mountain Branch), found out where the deer were “working,” and after a night of wild poker playing (no drinking) and a few hours of sleep followed by a gulp of black coffee boiled in a large pot with no grounds holder, we went up the ridges in the dark to the saddle passes.

There we waited for the “big-city” hunters to come up at their leisure and with their loud talking and frequent crunching of fallen twigs and kicking of pebbles effectively drive the deer ahead of them. It worked like a charm.

Every man in the party got at least one shot, while two—my brother and his friend “Spikehorn”—got one buck each.

Unfortunately, since Jack and “Spikehorn” were the youngest in the party, they had been plied with tales of how tough the mountain deer were and how hard they were to bring down and keep down. So both went out and got 220-grain soft-nose ammunition for their .30-06s.

Spikehorn’s one shot decapitated his deer, blowing away all but the skin on the nape of the neck. Henceforth he was known as “Cannonball.”

Jack’s deer went down on the other side of a deep ravine but in sight, where it lay trying to get up. At each movement, Jack pumped in another “cannonball.” At least the liver could be eaten. The rest had to be thrown away.

My father missed his chance because he had done his climbing with the chamber empty as a safety precaution and, when he got on stand, forgot to lever in a round. In the time it took to work the bolt of the Model 70, the deer was gone.

Several more mornings of climbs in the frosty dark, standing and waiting, bore no more results—except that probably we all suffered heart damage. Nobody took the time to clean out the three-gallon coffee pot, but instead just left the residual coffee and soggy grounds in it while adding fresh ground coffee and water each night.

After a couple of cups of that at 4 a.m., you could be all the way up the mountain before your heart stopped pounding on the verge of fibrillation.

As a prelude to that Woodland Valley hunt on Cornell, Wittenberg, and Slide Mountains north of Peekamoose, one of the fellows—Fred—found that he could get no ammunition for his .300 Savage.

So, the night before we left for the cabin and while on the way to a semi-formal dance in our fedoras, black raincoats, and white silk scarves, we did a search for ammo. We were all in my dad’s 1934 Packard, a car that was big, black, long, and looked like it came out of a set for The Untouchables.

Being in a hurry to pick the girls up and get to the dance, I was moving pretty fast from place to place, pulling up in front in a roar of tires and much dust.

At one of these places—which we thought was a sporting-goods store—the stop was rather dramatic, and then, to add to the drama, we all jumped out and headed for the place, bursting in the front door to see the several occupants become very still while reaching beneath their counters.

The door to the rear, which was normally closed, was open, and through it I could see a wall-sized blackboard with the tallies from horse races across the country scratched on in white chalk.

We had blundered into a betting parlor (strictly illegal in those days) and were obviously mistaken for hoods from a rival mob who were dropping in to make trouble or demand a piece of the action.

As I took in the picture, I realized very quickly that we could be in much trouble ourselves. So I walked up to the proprietor, who still had his hands beneath the counter, and said in a clear but somewhat shaky voice:

“Do you have any .300 Savage ammo?”

The sighs of relief from their side of the counter were highly audible. We were very sober as we drove on to pick up our dates and go to the dance.

At a later—and, as it turned out, my last—expedition with my father (and youngest brother, Tom), I had the unique experience of having to hitchhike while dragging a dead but still warm deer back to where my father and brother were on stand. They had the car.

As before, Dad had talked to his acquaintances in the Wallkill Valley near Mohonk Mountain to find where the deer were. He then dropped me off in the pitch dark of a frosty late November morning with instructions to walk into the woods a few hundred yards and settle down for a while to let my scent drift away. He had previously gotten permission from one of the Smiley brothers to hunt on the Mohonk Mountain House preserve there.

Almost at first light I heard a scratching sound directly in front, but thinking it was a squirrel, ignored it. Then, as the light improved, I saw that it was a browsing, beautiful, forked-horn buck.

As I dragged it out to the road, I met a party of “city” hunters dressed in Abercrombie & Fitch’s best, who were a bit dismayed at the thought of having lost a deer because they had that extra helping of pancakes at the motel before they left.

The first car to come along picked me and the dead deer up and drove us right to my father’s car, who immediately tied the deer on the right front fender of his ’34 Packard and drove Tom and me down to a diner in New Paltz to have ham and eggs. He was very proud.

As an alternative to Dad’s conversations with “natives” to find where the deer were “working,” I tried spotting them from the 55-horsepower Taylorcraft that I had learned to fly while a junior in high school.

That effort was only marginally successful in valleys where the deer would come out into the cultivated areas and orchards to browse on apples and other produce very early in the morning before they went back up into the hills for the day.

But it was never successful when they were in the woods. Their marvelous protective coloration made them essentially invisible from 500 feet up. And besides, even at that altitude in narrow mountain valleys, I was much too busy staying alive—especially as the upper valleys turned to gorges and ravines—to dwell too much on the spotting of deer.

So Dad’s technique remained our standby.

My last hunt—except for numerous excursions while at St. Lawrence University in Northern New York State to help local farmers rid their pastures of woodchuck—was on Rose Mountain in the upper Esopus Valley above the Ashokan Reservoir in the mid-Catskills.

As I came down off the mountain after an early morning hunt, capped by a sandwich lunch seated on a crag overlooking miles of hills, valleys, and habitations below, in a silence so complete that I imagined I could hear the few, puffy cumulus clouds as they traversed the cobalt sky, I followed an abandoned lumbering road downward.

Well down on the southern flank of the mountain, I saw below me and several hundred yards to the right a group of “hunters” lounging on a small, grass-covered knoll. The “woods” road I was on took me below the knoll into a heavily wooded area about 500 yards from the “hunters.”

The first crack of a high-powered bullet passing close by me was startling, but as they continued, I dove into a ditch alongside the road and there listened to the slugs smack into nearby trees and turf. Apparently the “hunters” on the knoll had seen the motion of me walking beneath large, old, leafless trees but didn’t wait to determine whether I was man or beast—much less buck or doe—before they opened up.

As the barrage continued I realized that with my scoped Model 70, 250–3000, I could have put out either eye of each of them, but decided instead to wait until they tired of their fun and went back to their bottle.

It was at that point that I really began to feel what the game must feel and so, with few exceptions, thenceforth did my hunting with a camera and my woods-hiking out of deer season.

And I’ve enjoyed every minute of it—until the effects of a ten-year battle with leukemia and six years of chemotherapy put an end to the heavy-duty hiking such as I had done in March ’88 in the mountains of Northern California, where the vistas were magnificent, the ultraviolet damagingly intense, and the brown vultures annoying as they made very close rear-to-front passes over my head to sniff and determine if I would soon be a meal.

But I can still enjoy the sweet, pungent fragrances and cathedral-like silence of the woods, the early mornings at nearby reservoirs as the tendrils of mist slowly ascend at the urging of the orange, rising sun, and the mallards, Canada geese, and other species leave their chevron wakes on the mirror surface as they swim out just far enough from shore to escape any possible closer attention.

And then, as I’ve learned to let my trace of Iroquois genes take over, I’ve learned to walk so quietly, peaceably, and unobtrusively that many times I’ve gotten within arm’s length of the Canada geese—even with their young present—embarrassingly close to deer (they are so vulnerable, as long as I’m downwind), families of raccoons, snakes, and very close to many other game species.

They are quick to sense if you are hostile or peaceable and, barring sudden moves, will allow a slow, close approach as long as you have nothing in your hands that might appear to them as a weapon. That close approach permits a much fuller appreciation of the exquisite beauty of their markings and their living bodies.

And you also get to hear the low warning sounds they make (geese in particular) as your proximity begins to make them nervous. Just don’t show any fear—even as you remember that one angry, fully grown Canada goose can break your arm with its powerful wings.

In fact, on a few rare occasions, after I’d sat very quietly on the ground, squirrels and even some bird species have climbed up on my arms or shoulders. This, however, ended abruptly when a squirrel, while exploring my right shoulder and that side of my head, decided that my ear lobe looked like a tasty morsel and began nibbling.

Even in heavy rains, I’ve trudged the trails in my Gortex outfit listening to the drip of the rain as it descends from leaf to leaf. Then the only other humans seen are the mushroom gatherers.

Every moment, to paraphrase the song, has a meaning all its own in the woods as the lighting intensity and angle change, the temperature and precipitation change, and the breeze veers. And as the seasons go from the deepest of winter—with the thick ice in the reservoirs booming as it contracts and cracks—thence to spring, to summer and fall, other dimensions of beauty and tranquility are added.

This cathedral of nature, with its living oak buttresses and its ever-changing rose windows of sky and clouds, is a serene place to meditate on Brother Death as the leukemia progresses and to feel that I’m no longer the enemy of the wildlife, but their friend and brother.

No comments:

Post a Comment